Derniers numéros

I | N° 1 | 2021

I | N° 2 | 2021

II | N° 3 | 2022

II | Nº 4 | 2022

III | Nº 5 | 2023

III | Nº 6 | 2023

> Tous les numéros

Dossier : Du rythme, entre schématisation et interaction

|

An Essay on Rhythm Eero Tarasti Publié en ligne le 30 juin 2022

|

|

|

Rhythm is a concept or phenomenon which concerns almost everything between heaven and earth, the human body, biology, nature, cosmos, person, social institutions, arts and values. Taking into account its universality, it has not been studied that much. Almost all semiotics theories have adopted achronic and taxonomic models, especially Greimas’s grammar and Peirce’s triadic model. In what follows, I shall focus on how the being (l’être) influences the becoming (le devenir), delaying it and, in extreme cases, closing it, whereas the doing (le faire) activates it by accelerating the musical pulse and the proceeding of the time. Seen from this perspective, linear events launch two fundamental processes, namely expectation and remembering. According to the definition given in the first volume of Greimas’s Dictionary, it is clear that rhythm is not only an expression, a signifier, but is linked with semantics1. In a historical overview, we shall see what consequences this idea will have regarding the definition of rhythmic genres. The definition proposed in the second volume is broader : there it is stated that in its formal aspect it can be determined as a binary phenomenon playing on the relation between the discontinuous and the continuous, between consecutive elements and simultaneity. The notion of periodicity, combining the binary accentuation into a spatial expansion, leads to conceive of rhythm as a semiotically built object. Greimas also notes that rhythm is connected with such movements of the body as heartbeat, inhalation / exhalation, tension and detension of vocal organs. The whole field of semiotics and biology opens here and one has to discover the right rhythmic Gestalt to solve it. Only more recently occurred the turn to phenomenology : one can also semiotically investigate qualitative phenomena of the psyche. Existential semiotics appeared in the year 20002 while biosemiotics was still at its initial state with its seminars in Imatra (ISI). |

1 A.J. Greimas and J. Courtés, Sémiotique. Dictionnaire raisonné de la théorie du langage, Paris, Hachette, 1979, p. 319. 2 See E. Tarasti, Existential semiotics, Bloomington, Indiana University Press, 2000. |

|

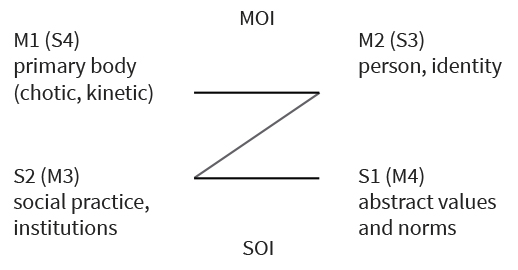

The literature on rhythm can be divided into two groups : i) ontological reflections and philosophies of temporality (Bergson, Jankélévitch, Daniel Charles, Husserl, Heidegger, Jaspers) ; ii) approaches to rhythm as an empirical phenomenon to be encountered from cultures (with their birth, rise, decline, vanishment) to particular manifestations, especially artistic ones. One might speak about micro- and macro-temporalities. Does History have a rhythm ? The simple saying that history repeats itself or the idea of an eternal return both refer to this possibility. If we keep within the borderlines of structural Greimasian semiotics, an essential distinction concerns the question whether rhythm appears in the realised utterance (l’énoncé) or in the act of utterance (l’énonciation). In poetry, rhythm is either a quality of the text itself and one of the features which distinguishes it from prose (as Juri Tynianov shows in Le vers lui-même3) or it may appear only when a poem is recited. This distinction looms in the background of all rhythmic analyses and theories. The temporalisation of the Cartesian models of Greimas led ultimately to my present zemic4 model (the semiotic square now appearing as only a very distant starting point). According to this model, which is at the core of my existential semiotics, four positions have to be distinguished. In relation with rythm they may be characterised as follows : — Moi 1. Rhythm is corporeal, like in dance and sports. The pioneering work by the Finnish gymnastic teacher Kirsti Kemppi will serve here as my starting point. — Moi 2. Rhythm is psychological. Lerdahl and Jackendoff start at this psychological level. More generally, subjects always have their own time and tempo and rhythm in a broad sense. I call this species of rhythm actorial rhythm. |

3 J. Tynianov, Le vers lui-même, Paris, UGE, 1977. 4 “Zemic” for the simple reason that the orientation between its components takes the shape of the letter z. |

|

— Soi 2 appears in various dances, beginning from baroque. In poetry, it corresponds to the idea of meter as something socially established. The beat span theory of Ilmari Krohn as well as that of Alfred Lorenz is, as such, impressive but its practical applications are mechanistic. This genre is rhythm as social praxis, as convention. — Soi 1 refers to the aesthetics of rhythm in various cultures, to the mythologies associated with rhythm ; like Spengler, one can characterise different cultures and nations somehow stereotypically by their rhythmic qualities. This is rhythm as symbol. I shall contemplate different occurrences of rhythm and try to articulate the whole field in the framework of the following model which is based on the distinction between the above four modes of being : Moi 1 or body ; Moi 2 or person ; Soi 2 or social praxis and Soi 1 or values and norms.

The Z-model |

|

|

Corporeal rhythm is the starting point of many rhythmic theories, although they may later on be detached from this biosemiotic ground. The bodily rhythm is considered by many theoreticians as a simple relation of tension / detension. The idea is thus presented by such a classic musician as Wilhelm Furtwängler : Classical music (…) corresponds to man’s biological preconditions. What are these biological presuppositions ? For the first, there is the problem of tension and relaxation. All life moving in time reflects the rhythm of life ; as long as we breathe, we are either in movement or in rest. They organically belong together. The state of rest is earlier, more ?original’ so to say. One of the basic principles of modern biology is that for instance in many complex activities of the body (when singing, playing a piano or a violin, even when riding or skiing etc.) the detension is quite decisive.5 |

5 W. Furtwängler, Keskusteluja musiikista, Porvoo, WSOY, 1951, p. 128. |

|

About the corporeal origin of musical rhythm, one may initially refer to the doctrine of the American Alexandra Pierce about “Generous Movement”, a practical guide to the right movements in everyday life which takes into account the connection between bodily movements and music : Tonal music with its shapely melody, self-supporting harmonic progressions, incisive rhythmic figures and articulation into phrases that have climax and completion has qualities like those we are seeking in our physical movements. (...) Music is not a casual accompaniment to the processes but an active guide to the pace, the shape and the overall feel of the movement.6 |

6 A. and R. Pierce, Generous Movement. A Practical Guide to Balance in Action, Redlands, Balance Press, 1991, p. 14. |

|

Such reflections in which rhythm is a consequence of the bodily movement, “beat”, the rhythm of movement and dance concern rhythm as an act of uttering (énonciation). Even a most orthodox semiotician could hardly regard the moving body as a “text” (énoncé) to be read like a score. K. Kemppi observes that in both music and movement, rhythm is the force holding everything together ; in both, in addition to form, it includes the processes of tension and relaxation, dynamics and alteration of fastness7. Kemppi quotes Eino Roiha, who first introduced music psychology in Finland : rhythm is a time shape as well as a spatial shape (in visual arts, architecture, etc). However, when speaking about rhythmics of movement, we cannot ignore, according to Kemppi, the Swiss composer and music pedagogue Emile Jacques-Dalcroze and the rhythm education method he developed. Rhythm was taught by movement. Rhythmics then meant either a dance-like improvisation based on the use of percussion, or gymnastics accompanied by music, whose purpose was to develop musicality, particularly the rhythmic talent. |

7 K. Kemppi, Liikuntarytmiikan perusteet, Porvoo, WSOY, 1969, pp. 1 and 3. |

|

Poetic measure or metrics is closely linked with musical rhythmics, but it is limited to the study of phenomena of measure. “Movement is poetry of body”, states Kemppi. To the same result had already come the Swiss Ernst Kurth when speaking about the “kinetic energy” of music. When we shift from rhythm to movement or from movement to rhythm, we have a rhythm experience, which touches our innermost being. It searches for echo in our particular rhythm and manifests itself through movements. Rhythm experience is the mysterious spark which, for a fleeting moment, makes us feel unexplainable pleasure and liberation, and makes us throw ourselves to the pulsation of existence, to the experience of living, affirmation, plénitude. Next, Kemppi introduces the smallest units of rhythm in correlation with the movements of the body as, for instance, in different types of clapping. Spondee or the equal tones tam-tam, the full-length taa, dactyle tam ta-ta, counterdactyle tata – tam, four notes tata tata, middle long ta-tam-ta. Beginning long : tam-ta, final long ta-tam, upbeat tam ja broken beat tam. Each beat span gets a semantic characterisation ; full long or spondee is tranquil, vanishing, dactyle is fluent, counterdactyle surprising, four-note is light, gracious, flippering. The same characterisations are repeated for three beat meters. Judith Lynne Hanna, for her part, starts with the statement that “dance is a cultural behaviour”8. In our terms it belongs to the world of Soi 2. She quotes Ray Birdwhistell : Men move and belong to movement communities just as they speak and belong to speech communities. (...) Dance has the characteristics of intentional rhythm, nonverbal body movement and gesture. (...) there are kinetic or corporeal languages and dialects (…) they contain motoric behaviour in patterns which are closely linked to musical features. Yet, the repetition or redundance is not always typical of dance, its climaxes can be unique patterns. It is not clear how motoric patterns are combined with the equivalent features of musicality (…) perhaps it is music that participates in determining traits of dance. Or perhaps the psychobiological foundations produce both.9 |

8 J.L. Hanna, To Dance Is Human. A Theory of Nonverbal Communication, Austin, University of Texas Press, 1979, p. 3. 9 R.L. Birdwhistell, Kinesics and Context. Essays on Body Motion Communication, Philadelphia, University of Pennsylvania Press, 1970, p. 4 and 21-23 (our stress). |

|

In this context, what does the notion of intentional rhythm mean ? Rhythm refers to a patterned, temporally unfolding phenomena. Physical work10, sports, playing of instruments and, sometimes, fear and anxiety are typically rhythmical. Therefore, dance has to involve more than just rhythmical movement, namely the pulsing flow of energy in time and space11. Hanna noticed that biological time focuses on rhythm in man’s organism and in all automatic functions of the body, like brain, muscle tensions, heartbeat and breathing, hormonal functions. Some think that even speech has a biological rhythm. |

10 See Karl Bücher’s classical work, Arbeit und Rhythmus, Leipzig, Teubner, 1899. 11 Cf. J.L. Hanna, op. cit., p. 29. |

|

Presenting various cases, from rhythm in rock paintings to rhythmic schemes of culture, Hanna states that all have also their aesthetic dimension, which opens in the direction of Soi 1. In the web seminar previous to the present dossier, Peer Aage Brandt presented prehistoric pictures which portrayed dance and its rhythm by broken lines and musical beats by dots (probably first musical notations)12. From our perspective, Hanna’s inquiry represents the case in which the rhythmic analysis begins corporeally with units of Moi 1 and ends up on social-cultural dimensions of rhythm, that is to say the level of Soi 2. |

12 See, in the present volume, P.Aa. Brandt, “La petite machine de la musique”. |

|

Most rhythm theories, from Ilmari Krohn to Fred Lerdahl and Ray Jackendoff’s generative model, are based upon a kind of anthropomorphic structure which involves actorial effects. Ilmari Krohn’s starts in the following manner : “In the art music, rhythm (...) can be compared to the inner pulsation of organism or to the structure holding it together”13. In the first edition, dating from 1911, the connection to corporeality was made still more visible by drawings. The central concept of Krohn, the beat span (iskuala in Finnish) assumes the status of the structurally smallest unit of meaning, permitting to form larger units by ars combinatoria. He considers Hugo Riemann’s rhythm theory one-sided when it underlines the musical development of motifs (i.e. actoriality, we would say). He proposes that legato slurs were used to indicate phrases and groupings, which are limited to the tiring uniformity of a paired articulation : beat span = 1 bar, phrase = 2 bars, row (Reihe) = 4 bars and period = 8 bars. Even poems have to be inserted to this quadrangular rhythm of phrases ; number 4 is the basic number of rhythm which leads to the archetypal musical actor, which we experience as the most complete representation of man’s person, Moi 2. Nevertheless, in what follows, Krohn admits that rhythm exists both in art and life. One may call rhythm any relationship of parts to the whole. Rhythm means the relationship of large as well as small parts of a musical work to that whole to which they belong. The artistic effect of any tone or tonal group is based upon its relationship to another tone. One might say, from a linguistic point of view, that what is involved is the distinctive feature of rhythm, either as opposition or otherwise. |

13 I. Krohn, Course of Music Theory I. Rhythm (Musiikin teoria oppijakso 1. Rytmioppi), Porvoo, WSOY, 1958 (2nd ed.). |

|

Krohn then lists the rhythmic units of his theory : 1) beat span, or foot in poetry ; 2) pair of beats ; 3) phrase, or verse in poetry ; 4) pair of phrases or verses ; 5) utterance or period ; 6) section (säkeistö, taite) ; 7) form, like lied form (sikermä) ; 8) part, for instance in a sonata the exposition, development, recapitulation, transition ; 9) yksiö, such units as for instance in a sonata allegro, adagio, scherzo and finale ; 10) kehiö, suite, like a whole sonata ; 11) complete work, like opera, oratorio ; 12) series of works (täysiösarja), like trilogy, tetralogy. Krohn defines the beat span as follows : “Rhythm emerges when the time span needed to perform a composition is systematically divided in a manner which is conceivable to the ear” (p. 23). Tones are either accented or not, and we call the time span between two consecutive beats “beat span”. This view is common to many actorial rhythm theories but as a contrast to it, there is the idea that rhythm stems cinetically from energy (Ernst Kurth) or rhythmic activity (Jan LaRue), which aspect foregrounds the continuity of the rhythm phenomenon, not its discrete quality. The theory is the same at Vincent d’Indy’s : the syllables of speech so to say get musicalised by the force of modalities via two types of accents : accents toniques and accents pathétiques14. |

14 See E. Tarasti, A Theory of Musical Semiotics, Bloomington, Indiana University Press, 1994, pp. 39-40. |

|

After having examined the regular beat spans of different meters, Krohn observes that in tonal art, there is no fixed unit according to which one could measure the beat spans. The note values are relative and depend on tempo. They refer not only to the speed of measures but also to their atmosphere. Here Krohn’s theory repeats the views of 18th century scholars Mattheson and Rousseau. He lists : grave, largo, adagio, maestoso, andante, moderate, allegretto, allegro, presto and mentions their additional characters (aspectual semes in semiotics), con espressione, con moto, con fuoco, agitato, appassionata, scherzando, vivace. The atmosphere of the tempo indication is not at all without sense in the judgment of measure. Yet, it is often to be discovered only so to say in the end. Every musician knows this through practical experience15. We are here at the core of actorial rhythm in music. The analysis of Robert Schumann by Roland Barthes in “Rasch” is a remarkable example16. To his mind, Schumann’s music represents the beatings of the body. Battement is its central notion. Without knowing, Barthes was thus a Krohnian analyst. |

15 Cf. J.-J. Rousseau, Dictionnaire de la musique, Paris, Chez la Veuve Duchesne, 1767, pp. 410-419. 16 R. Barthes, Le plaisir du texte, Paris, Seuil, 1975. |

|

Krohn introduces rhythmic structures inspired from classical Greek terms (with funny Finnish translations), like spondee (plain tone or broken bar) and then proceeds into more extensive formal units. A real system is built, a framework for the model of music analysis which became the dominant method in Finnish musicology until the 1960s. Finally, Krohn proved the validity of his method in his great Sibelius and Bruckner studies. But they were rejected, both in Finland and elsewhere. He remained faithful to his thought that music is expressive and semantically loaded, that it has a programmatic content, a hermeneutics but this met even less understanding. Supposed to shift from the corporeal rhythmic to the actorial, Krohn ended at a certain romantic praxis and aesthetics and suffered a failure on this level. No better was the case of Krohn’s soul mate Alfred Lorenz whose Wagner analyses were built in the same way from smallest units to larger wholes, but were, as to their final outcome, as hopelessly rigid apparatus as by Krohn. The rhythmic formation of a composition can take place in various ways, says Lorenz. He distinguishes five cases : 1) rational rhythmics, 2) melodic elements like motives recurrences, 3) the alternation of harmonic elements between tonic and deviations from it, 4) dynamic elements and even 5) mere sound colours17. He analyses scenes from Wagner’s operas counting the numbers of their measures and ending in exhaustive diagrams. The procedure is the same as in Krohn. From the smallest structural units, one gathers by ars combinatoria larger units which can always be reduced to the smaller units of the basic level. So, form dissolves into endless numerical charts and does not lead to qualitatively levels. When we add here leitmotifs and themes, we reach the concept of symphonische Gewebe, symphonic texture. In other words, Wagner’s music is returned to a symphony. Lorenz’s scheme tells very little about what really happens in music although he makes relevant observations. His system of rhythm analysis rises from the actorial level to the social one of S2 and from there to the aesthetic one or S1. |

17 A. Lorenz, Der Ring des Nibelungen, Tutzing, Hans Schneiding, 1966, pp. 13-14. |

|

In the need of more evidence about actorial rhythmics we shall now direct our attention onto Lerdahl and Jackendoff’s generative theory of tonal music, which was in fashion in the 1980s but passed through the fate of helpless outdating rather soon18. They start from the fact that music cannot be only the psychology of music, that is to say something actorial. Their objective is a “formal description of the musical intuitions of a listener who is experienced in a musical idiom” (p. 19). In the background, there is of course Chomsky’s generative theory and its ideal speaker (p. 2). The crucial notion is that of “experienced listener” or competent music listener. When a listener hears a work, he organises the sound signals into such units as motifs, themes, phrases, periods, theme groups, sections and the piece itself. Performers in general try to breathe rather in the intervals of these units than during them. At the same time, the listener instinctively infers the regular pattern from strong and weak beats to which he correlates the musical sounds. The conductor waves his stick and the listener taps his foot in certain moments of the beats. Our term for these patterns is meter. The most important is that musical groups are heard hierarchically. The motif is heard as a part of a theme, the theme as a part of the theme group and the section as a part of the piece. Hierarchy means that some of these elements with their areas subordinate or include other areas. Then the authors clarify the notion of accent and find three species of it : phenomenal, structural and metric. Phenomenal means whatever point on the surface of music, which stresses some moment in the musical stream. To this belong such events as attacks of pitches, local accents like sforzandi, sudden dynamic or timbral changes, long and short leaps to high pitches, changes of harmony, etc. Structural accents are caused by the emphases of melodico-harmonic points in a phrase or section, especially in cadence. Yet, regarding the global form of a composition, the Chomskyan tree structures do not help much because they are as schematic as Lorenz’s Stollens and Bars. |

18 F. Lerdahl and R. Jackendoff, A Generative Theory of Tonal music, Cambridge, MIT Press, 1985. |

|

Jan LaRue’s classical Guidelines for Style Analysis is quite different insofar that it does not aim for any axiomatic articulation of rhythmic element but takes into account the many-sidedness of the phenomenon19. Rhythm is a parameter that finally leads, on the macro level, to the category of style analysis called Growth, which means a reevaluation of corporeal rhythmics at the end phase and not at the starting point of the form analysis. Here, the observation of rhythm or actorial rhythmics leads out of a hermetic system to a completely different level. LaRue first notes about rhythm that it is fundamentally ambiguous, the most problematic of all musical elements. He distinguishes two aspects (pp. 88-90), as follows. First : rhythm is a layered phenomenon. And it is blended with the movement in the principle of Growth, which completes the effect of rhythm at the macrolevel. Rhythm and movement are joined ; the rhythms on small scale contain rhythmic-durational impacts, whereas the movements contain more general outputs (broader, less definable interaction like the Gestalt rhythm and textural rhythm). Rhythm and movement should not be separated. The movement on the middle and large dimension does not coincide necessarily with the rhythmic accents on the small dimension. In the comprehension of rhythm, we cannot always resolve these conflicting stresses into a single, simplified pattern (p. 89). Second aspect : stress is variable in duration. Release of tension is not necessarily instantaneous and, as a result, durations of stress will tend to reflect the dimension affected. Then LaRue wants to expand rhythm into larger dimensions. He introduces the following : 1) continuum goes beyond meter to represent the whole hierarchy of expectation and implication in rhythm. Tempo is the speed of operation of the continuum, typically governed by the speed of the controlling pulse. Changes in tempo indication obviously influence rhythm in all dimensions (pp. 90-91) ; 2) surface rhythm includes all relationships of durations, assumed to be approximately as represented by the symbols of notation ; 3) interactions result when the events in other elements approach a condition of regularity that can be felt either as reinforcement of the continuum or as patterning related to surface rhythms. It seems that much of the difficulty in understanding rhythm arises from a failure to appreciate the many and various sources from which the Movement is generated. The idea of thesis and arsis (downbeat and upbeat) borrowed from prosody is confusingly irrelevant to music. To understand rhythm, we should first postulate a spectrum of intensity ranging from low to high activity. Rhythmic functions are not fixed but relative to each composer and style. In principle, one can distinguish three states of rhythm : stress (high levels of activity from any source), lull (or pause, a temporary stability in the rhythmic flow) and transition (or preparation for a situation of stress). Finally, rhythm requires several events in conjunction before we can sense the happening of movement. 1) Middle dimension stress may conflict with a small dimension accent, just as melodic stresses do not necessarily coincide with points of highest harmonic activity. 2) Between articulations, one may find stresses for each rhythmic layer (continuum, surface rhythm, interaction). Rhythm as such can act as a theme (for instance, the main theme of the 1st movement of Beethoven’s Waldstein just consists of its pulsating energy). But there are aesthetic aspects as well. For instance, what is the right performance tempo of the Allegretto of Beethoven’s Seventh symphony ? We have to determine a composer’s characteristic rhythmic module, the size of gesture or idea that seems most often to occur. One could almost speak of rhythmic obsessions of a composer in the same way as Charles Mauron argued about obsessive myths of writers. When such a mode has been found one has to specify it : SLT (stress, lull, transition), TSL (middle stress), TS or LTS (late stress). And finally rhythm in small dimensions. It is then possible to shift from the level of rhythm to the principle of Growth. Jan LaRue’s merit is to avoid a generative system. Probably with his method, one gets results particularly from the unique and individual use of rhythm of composers, whereas Krohn, Lorenz and Lerdahl / Jackendoff tell more about their own systems of rhythmic analysis than they are sensitive regarding their objects. |

19 J. LaRue, Guidelines for Style Analysis, New York, W.W. Norton, 1970. |

|

To this category belongs also the Twentieth Century Music, by Stefan Kostka and, particularly, its chapter, “Developments in rhythm”20. In a way, this examination already belongs to our next category, namely praxis of rhythm in society and various phases of its history : in other words, rhythm as a genre. Since Kostka starts with a definition of rhythm, it is worthwhile to notice how in general the scholars define these principles, although in somewhat different ways : Rhythm – the organisation of the time element in music Syncopation is a term used either when a rhythmic event such as an accent occurs at an unexpected moment or when a rhythmic event fails to occur when expected. Here Kostka foregrounds the problem “written rhythm” vs “perceived rhythm” or that problem which was above referred to as the distinction between utterance and act of uttering (or as it was put by Lévi-Strauss, as the distinction between thought-of models and lived-in models). In this case, uttering concerns the receiver and not the sender. |

20 S. Kostka, Materials and Techniques of Twentieth-Century Music, New Jersey, Prentice Hall, 1999. |

|

Then arrives the category of ametric music21. Gregorian chant is a good example as is much of electronic music. Some writers use the term “arhythmic” for music in which rhythmic patterns and metric organisation are not perceivable. However, music can well be ametric but never arhythmic. Obviously, the pulse exists. Some conductors are able to discover it even in the most complicated avant-garde pieces. For instance, Stravinsky’s Sacre sounds so ametric that one could believe that there is no metric element at all. Such is also the case of Berio’s Sequenza no. 1. Next, come the added values and non-retrogradable rhythms. A non-retrogradable rhythm is a rhythmic pattern that sounds the same whether played forward or backward, like rhythmic palindromes. Tempo can also be modulated and thus come to polytempo. One can also speak about serialised rhythm and isorhythm. “Isorhythm” refers to the use of a rhythmic pattern that repeats using different pitches. If the rhythm and pitch pattern are the same length, we use the term ostinato rather than isorhythm. However, one of the rules of modern serial music was to avoid repetition. It was of course a consequence of seriality, but in his aesthetics, Adorno used ostinato as proof of a catatonic disturbed state of a subject in the psychoanalytic sense and doomed Stravinsky on this ground in his philosophy of new music. In this case, the actorial débrayage continues until the level of Soi 1 or aesthetics. Kostka’s treatise is an excellent illustration of how the actorial rhythm dissolves in contemporary music. |

21 See S. Kostka, Materials and Techniques..., op. cit., p. 122. |

|

In the end, one has to scrutinise a theory of actorial rhythms which also dwells on the level of symbolic rhythm : the doctoral dissertation, by the Venezuelan scholar Drina Hocevar, Movement and Poetic Rhythm22. Her starting-point was, on one hand, Heidegger’s philosophy and existential semiotics, and the poetry of Emily Dickinson, on the other. She also went through different theories of rhythm and metrics and, at the same time, created her own theory. Hocevar refers to Greimas’s dictionary, where rhythm appears as a forme prégnante, a term borrowed from René Thom meaning forms which are biologically significant concerning the survival of species (p. 90). She also refers to Floyd Merrell’s theory according to which text is a kind of dance. Movements of dance are a spontaneous flow based upon a certain competence, but when the dancer becomes one with his dance, then, in fact, he is not dancing but the dance dances in him. Hocevar sees an analogy between Merrell’s “dancing dance” and Heidegger’s language (and one might add the Lacanian ça parle). Rhythm seems here to transcend the subject. Following Heidegger, the temporality is not an entity but it temporalises itself. The question is how being is to be understood in relation to time (the same could be said about the relationship between zemic and time, I would add here !) The being in the world or Da-sein is based upon the disclosedness. This is linked to truth and care (the concept of Sorge). Care has been understood as the existential meaning of its being which is based upon its temporality. In Heidegger’s view, the original time structure gives rise to the ordinary understanding of time. He interprets the everyday use of the clock phenomenologically and examines how our everyday understanding of time is manifested. The now has the character of transition. It appears in what is counted or calculated. The nows are not isolated points but rather follow the flux of time : the not yet now and the no-longer now give rise to present, future and past. Yet, there are two basic modes in which the future temporalizes itself : the authentic and inauthentic ; inauthentic as the future is characterised by its potentiality for being while authentic is an act of expectation. If time temporalises itself then rhythm rhythmicises itself. Sayantan Dasgupta, a young Bengali semiotician has found out that Dasein is a museum of past events. Time has separated them from us and pushed them at a distance ; this is what he portrays by the notion of interpassivity of Dasein. Furthermore, classical is Heidegger’s concept of attunement of the being, its atmosphere or Befindlichkeit which is the primary property of the Dasein. Moreover, Heidegger ponders Angst and fear regarding temporality, and, finally, the notion of collapse or Scheitern of time. All these issues have relevance in the philosophy of rhythm in its Soi 1 level. In the second chapter, Hocevar reflects on rhythm in music and poetry, starting from the definition of rhythm as a subdivision of a span of time into sections perceivable by senses, principally by means of duration and stress. She refers to the theory of John Dunk and Lerdahl / Jackendoff, for whom the intuition of tonal music is based upon metric structure, which means that the events of a composition are set in a regular alternation of strong and weak beats at a number of hierarchical levels. On the other hand, we have rhythmic grouping structure, which expresses the hierarchical segmentation of a piece into motifs, phrases and sections. Yet, Hocevar says that rhythm, unlike meter, cannot be explained in terms of a mathematical structure or grammaticality that leaves the affective dimension aside. Rhythm is our own selves (being) projected toward something (p. 106). |

22 D. Hocevar, Movement and Poetic Rhythm. Uncovering the Musical Signification of Poetic Discourse via the Temporal Dimension of the Sign, Helsinki, Acta semiotica fennica, XVII, 2003. |

|

An important chapter is dedicated to the metric theory of V. Zirmunskij, who defines both rhythm and meter by regularity23. The most important factor distinguishing poetry from prose in the orderly arrangement of syllables and stresses within the limits of line, period and stanza. For Zirmunskij, rhythm in poetry and music is established by the regular alternation in time of strong and weak sound (or movements). Alternation of accents in a verse results from the inner properties of linguistic materials and the norms set by the meter. Likewise, the Russian formalists emphasised the dynamic nature of rhythm in poetry. Andrej Belyj remarked that rhythm means the total quantity of deviations from the metric pattern. There are for instance several possible deviations from the iambic tetrameter. The only necessary stress on a line is the last one (or the one of the 8th bar), which means the end of the line and which is also indicated by rhyme. Belyj also notices that the more there are variables through the deviations from meter and the most unexpected and complicated the patterns produced by these deviations, the “richer” the rhythm of a poet, i.e. not only objectively more heterogeneous but also “better” in an artistic sense. The same standpoint is held by Juri Tynianov in Le vers lui-même, particularly about Ohrenphilologie or the acoustic study of rhythmic in poetry. He takes as an example of the rhythmics and metrics a poem by Pushkin in which the writer left without print three lines in its second edition. However, these lines existed and someone knowing the poem could imagine them at their proper place. The metric energy of the whole stanza was preserved untouched in this fragment. According to Tynianov, what is relevant is that in the uttering of the utterance, that is to say in reading, it can be completed. (These comments are not from Hocevar’s dissertation but my observations about these texts). |

23 V. Zirmunskij, Introduction to Metrics. The Theory of Verse, The Hague, Mouton, 1966. |

|

3. Rhythm in praxis and conventional rhythm We can now shift from the actoriality to the level of social practices and conventions, in which we are already detached from the bio level of Moi 1 and organisms, and continue, in a way, actoriality which becomes the technics dominated by the rules of the musical style period. Here, it is best to start regarding baroque music, both in Germany and France. |

|

|

The central authority who dominates the scholarship is Der Vollkommene Kapellmeister of Johann Mattheson from 173924. Although Mattheson emphasises that the art of writing a good melody (as a musical actor) is crucial in music, he dedicates his work mainly to rhythm. Mattheson defines rhythm via speech, since in the art of speech prosody teaches us where to put accents, what is to be pronounced as long or short. The meaning of the term “rhythm” is for him nothing else than the number. It deals with the counting of syllables in speech and musical works and with the measurement of their length. While in poetry one speaks of feet, in music and song one refers to “sound feet”, Klangflüsse. As an example, Mattheson offers the choral Wenn wir in höchsten Nöthen and its different rhythmisation giving rise to various dances, such as menuetto, gavotte, sarabande, bourrée, polonaise, which represent rhythm in social praxis. Thereafter, Mattheson applies certain feet from prosody directly to music (spondée, pyrrhus, jamb, trochee and, furthermore, dactyles, anapests, molossus, tribrachys and bacchus, and others). He too distinguishes two kinds of time spans. One concerns mathematical divisions, whereas the other is determined by the hearing, according once more to the dictinction between utterance and act of uttering. The first is called in French mesure, meter or time ; the other again is mouvement. Italians call the first battuta or beat of a measure and the other by some additional words : affettuoso, con discrezione, con spirito etc. The fundamental essence of bar is that it has two phases and that its origin is in pulse, inhalation and exhalation. Such corporeal qualities have been taken as their models by composers and poets who organised the measures of their melodies and verses according to them. What is involved is also a thesis and arsis. Yet, harmony reaches not only to Klang, a sound but also to its soul, the measure. What is the difference between measure and movement ? Mesure or meter is the way whose destination is movement. Movement can be very different in various measures, sometimes cheerful, sometimes flat as to the emotions or Leidenschaften which have to be expressed. The theories of Mattheson are, as one can see, thoroughly actorial. They are completed by the advice given by Frenchmen as to rhythm, meter, tempos and characters of dances. There, we are already shifted from actoriality to the praxis of rhythm i.e. to the social conventions and, by that way, to the course of music history toward absolute instrumental music. The statement of Francois Couperin fits well as a motto : Nous écrivons différemment de ce que nous exécutons — we write in a different way from how we perform (or utterance is also in music a different thing from the act of uttering). In the book, observations about different categories of adagio and allegro are gathered. |

24 J. Mattheson, Der Vollkommene Capellmeister. Neusatz des Textes und der Noten (1739), Kassel, Bärenreiter, 2008. |

|

Altogether, essential is that these tempos are cultural, they are Umberto Eco’s cultural units and not subjectively individual or actorial reflections of a subject. The same semantisation takes place in the characterisation in the arias and dances and their tempi allemande, aria, ariette, bourrée, chaconne, etc. All these dances of baroque survived till the latter half of the 18th century. Wye Allanbrook has studied them in Mozart’s tonal language, distinguishing particularly social characters of different dances and dividing the classical style into two poles : the learned (from its associations with school counterpoint, ecclesiastical, strict), and the galant, or free25. Ernst Kurth had already characterised the difference between these two styles and their role in the history of classical music : the former bound and linear style had its origins in the acoustics of Gothic cathedrals when the vocal parts were striving for the height without exact meter, whereas the latter was based upon body, walking, marching, dancing, it was earth-bound music and from it emerged what was above described as the actorial rhythm at its most typical as a four-bar period. Yet, in Allanbrook’s mind, the duple meters rhythm and meters of the learned style were reserved for expressions that were intended to have some connection with the ecclesiastical, while dance rhythms were regarded as the best way of portraying human passions. Allanbrook, just like in Mattheson’s work, then goes through different characters of various dance genres transferred to Mozart’s operas ; and in the end he launches his new category in connection to contradance, namely “danceless dance” (pp. 60-66). It is a dance that does not belong to any recognisable rhythmico-metric pattern but is still a dance. To my mind, the main theme of Mozart’s d minor Fantasy for piano is such a case. |

25 W.J. Allanbrook, Rhythmic Gesture in Mozart. Le Nozze di Figaro and Don Giovanni, Chicago, University of Chicago Press, 1983, p. 18. |

|

From here on, dances and rhythmic species, meters and measures became topics : march became a musical topic of the military sphere26, the triple measure, combined with the organ point of borduna on a fifth interval, produced the pastoral topics. The abrupt changes of measure and rhythms yielded Sturm und Drang. Menuetto was adopted as a movement in a symphony and, furthermore, it became a scherzo. Still, in the 19th century, waltzes were written as a symphony movement (Tchaikovsky). In opera music, even in Wagner, topics have their intensive life (as the “galloping horse” in the Ride of the Valkyries). They became musical narration just like the rhetorics of the baroque period. |

26 See R. Monelle, The Musical Topics. Hunt, Military and Pastoral, Bloomington, Indiana University Press, 2006. |

|

The rhythmical praxises are of course different in each culture. One may take as an example the Indian music tradition as studied by Lewis Rowell27. His book contains a chapter on time in Indian culture. It begins with a mythical poem that portrays the essence of time. Time created the earth ; in Time burns the sun |

27 L. Rowell, Music and Musical Thought in Early India, Chicago, University of Chicago Press, 1992. 28 Op. cit., p. 182. |

|

According to Rowell, this philosophy underlines connections between the ritual function of time and musical structure. In India, the idea of music emerged from religious ceremonies. The keyword was respiration. There were two coexisting streams of time : the external time of daily experience, manifest in the seasonal recurrences, daily routines, and the internal time devoid of divisions, motions, changes and other distinctions (p. 186). Gesture and breath, the motions of the hand and the outflow of breath are the archetypal forms of music-making. With the gestures of tala, the Indian musician regulates the illusion of outer time with its gross divisions and audible form, while manifesting the true, continuous, inner time with the emission of vocal sound. A crucial contribution of the Buddhist Jain and Yoga philosophers was their concept of time as a succession of discrete instants merging into the famous image of Buddha in a circle of flame by a whirling torch or in the illusion of a stream of water. The aim of the yogin was to perceive what exists between the successive instants, to reject the apparent continuity of experience and to seek freedom from illusion in all its forms by widening the perception of the moment in the attempt to find ultimate reality in what has been called a timeless present29. Equilibrium, Samya is the main purpose of tala and from this balance comes fulfilment in both this world and the text. The temporal process in music is reflected in the three phases of the cyclical evolution of the cosmos : the differentiation of primal matter, its division into perceptible forms ; orderly movement in structured time ; and finally, the dissolution of all created forms back into their original state of undifferentiated matter. After this, the cycle begins once again. The equation reads : equilibrium (rhythmic or cosmic) = division + time + rest. All three phrases are made manifest by actions, especially the hand motions of tala or Siva’s cosmic dance. In the printed Sanskrit source, tala is both a general term for the whole rhythmic system and a particular term to one of the eight hand gestures in which the left-hand slaps down audibly upon the right palm or the left knee. The single most distinctive feature of the Indian rhythmic tradition is the way time is made manifest by means of hand motions, claps, finger counts, and silent waves that accompany every performance. They are practical signals to the performer and, at the same time, mnemonic aids, the external manifestation of internal structure and energies. Then, rhythmic patterns can be presented by a notation which is using numbers just like in the Western beat spans. We get thus diagrams whose signs can be interpreted by notes and time values. After having pondered the role of metrics, Rowell states that, above all, the tala system deeply reflects the intuition of time in the Indian culture. One may therefore note that the Indian rhythmic system exploits, among the zemic levels, not only the body (gestures) or M1 but also Praxis or S2, and finally symbolism and ideology S1. |

29 Cf. R. Motiekaitis, Poetics of the Nameless Middle, Helsinki, Acta semiotica fennica, 2011. |

|

In the end, there is rhythm as a symbol and aesthetics. The different nations of Europe could be characterised, like in Oswald Spengler, by their primal rhythms ! Various nations are also imaginary entities as Benedict Anderson remarked in Imagined Communities. To this fictive character of a nation might well be added their typical rhythmical profiles, although one may here easily fall into stereotypes. According to Spengler, the primal figure of the European culture was Faust, whose fate was connected to time. He got all he wanted on earth from Mefisto until he made the mistake to say to the present moment : Remain here, you are so beautiful (Verweile doch, du bist so schön). If one thinks of the German culture, its basic tempo is andante as J. Langbehn said in his influential work Rembrandt als Erzieher (1989), in its time an impressive treatise. But the other aspect of Germanity is march, such as it appears in numerous works : funeral march of Beethoven’s Eroica, allegretto part in his 7th symphony which is the music for the funerals of Mignon at Goethe’s Wilhelm Meister (the knowledge of this literary tradition immediately has its impact on the interpretation of the work, its enunciation). Or the Ride of the Valkyries in Wagner, at the same time corporeal M1 and topical S230. The basic rhythm of the Viennese is naturally waltz but its general performance indication in enunciation is gemütlich, pleasant. In Hungary, rhythmics is diverse but its basic rule is Béla Bartók’s parlando rubato, which was heard in his piano playing and, of course, in the folklore of the region. The basic rhythmic identity of Italians could be tarantella, triple meter, but also the scanzione incitativa analyzed by Gino Stefani31. |

30 See R. Monelle, op. cit., pp. 72-110. 31 G. Stefani, Introduzione alla semiotica della musica, Palermo, Sellerio. 1976. |

|

The fundamental rhythm of Russia ? Innumerous examples from Glinka to Borodin i.e. from orientalism à la Polovetsian girls with undulating gestures (what Taruskin considered a particularly semiotic languish khora) or the polonaises and waltzes in the imperial style ; or the barbaric rhythms of Scythian style. Stravinsky’s Sacre’s rhythmics are, at the same time, exalted and calculated. In a film document, the young arrogant Pierre Boulez goes to meet the Maestro with the score of Sacre at hand and states : “There is a mistake in your Sacre, one bar too much !” Stravinsky takes the score, looks at it for a while and admits : “Yes, you are right ! There is one bar too much !” Finland ? Quintuple meter of Kalevala ? Det finska slutet. Brasil : not only samba but numerous dances from bossa nova to batuque and capoeira. North-America : of course, jazz, and linked to it that particular manner of enunciation which has been called swing or by the term grooving. It has been studied by Kristian Wahlström in his dissertation on Hard Rock Groove32. Wahlström defines this central phenomenon of popular music as follows : “to understand groove is not to apprehend it intellectually but to feel it through the body. (...) the term does not refer to a rhythmic pattern or a composed part which can be written in standard notation (…). Groove is here considered to transcend notation by emerging predominantly on the level of performance rather than the structural level of music, in other words, occurring mainly on the microrhythmical, nonsyntactical level”. So, cultures and nations have their own tempos, Werden or devenir principles which they often unconsciously follow and which also regulate the tempo and rhythm of communication. |

32 K. Wahlström, Student-Centered Musical Expertise in Popular Music. Pedagogy and Hard Rock Groove : a Design-Based and Psychodynamic Approach, Thesis, University of Helsinki, musicology, 2021. |

|

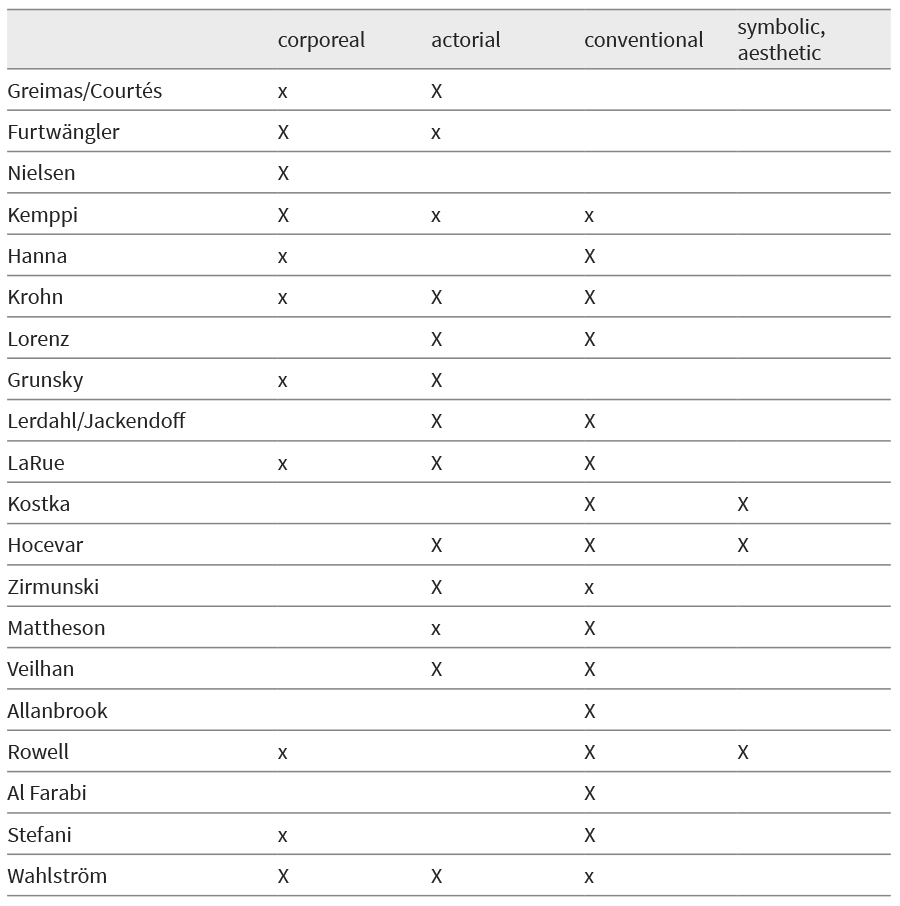

To conclude this review of rhythmic paradigms and variations we gather here, on a chart, different systems of rhythm analysis regarding the basic categories of our model, showing how it can serve as a metatheory of the world of rhythms :

|

|

References Allanbrook, Wye Jamison, Rhythmic Gesture in Mozart. Le Nozze di Figaro and Don Giovanni, Chicago, University of Chicago Press, 1983. Barthes, Roland, Le plaisir du texte, Paris, Seuil, 1975. Birdwhistell, Ray L., Kinesics and Context. Essays on Body Motion Communication, Philadelphia, University of Pennsylvania Press, 1970. Bücher, Karl, Arbeit und Rhythmus, Leipzig: Teubner, 1899. Brandt, Per Aage, “La petite machine de la musique”, Acta Semiotica, II, 3, 2022. Furtwängler, Wilhelm, Keskusteluja musiikista, Suomentanut Timo Mäkinen, Porvoo, WSOY, 1951. Greimas, Algirdas J. and Joseph Courtés, Sémiotique. Dictionnaire raisonné de la théorie du langage, Paris, Hachette, I, 1979 and II, 1986. Hanna, Judith L., To Dance Is Human. A Theory of Nonverbal Communication, Austin, University of Texas Press, 1979. Hocevar, Drina, Movement and Poetic Rhythm. Uncovering the Musical Signification of Poetic Discourse via the Temporal Dimension of the Sign, Helsinki, Acta Semiotica Fennica, XVII, 2003. Kemppi, Kirsti, Liikuntarytmiikan perusteet, Porvoo, WSOY, 1969. Kostka, Stefan, Materials and Techniques of Twentieth-Century Music, New Jersey, Prentice Hall, 1999. Krohn, Ilmari, Musiikin teorian oppijakso I Rytmioppi, Porvoo, WSOY, 1958. LaRue, Jan, Guidelines for Style Analysis, New York, W.W. Norton, 1970. Lerdahl, Fred, and Ray Jackendoff, A Generative Theory of Tonal music, Cambridge, MIT Press, 1985. Lorenz, Alfred, Der Ring des Nibelungen, Tutzing, Hans Schneiding, 1966. Mattheson, Johann, Der Vollkommene Capellmeister. Neusatz des Textes und der Noten, Kassel, Bärenreiter, 2008. Monelle, Raymond, The Musical Topics. Hunt, Military and Pastoral, Bloomington, Indiana University Press, 2006. Motiekaitis, Ramunas, Poetics of the Nameless Middle. Japan and the West in Philosophy and Music of the Twentieth Century, Helsinki, Acta semiotica fennica, 2011. Pierce, Alexandra and Roger, Generous Movement. A Practical Guide to Balance in Action, Redlands. Balance Press, 1991. Rousseau, Jean-Jacques, Dictionnaire de la musique, Paris, Chez la Veuve Duchesne, 1767. Rowell, Lewis, Music and Musical Thought in Early India, Chicago, Chicago University Press, 1992. Spengler, Oswald, Länsimaiden perikato (Untergang des Abendlandes) (1922), Helsinki, Kirjayhtymä, 1963. Stefani, Gino, Introduzione alla semiotica della musica, Palermo, Sellerio. 1976. Tarasti, Eero, A Theory of Musical Semiotics, Bloomington, Indiana University Press, 1994. — Existential semiotics, Bloomington, Indiana University Press, 2000. Tynianov, Juri, Le vers lui-même, Paris, UGE, 1977. Wahlström, Kristian, Student-Centered Musical Expertise in Popular Music. Pedagogy and Hard Rock Groove : a Design-Based and Psychodynamic Approach, Thesis, University of Helsinki, 2021. Zirmunskij, Viktor, Introduction to Metrics. The Theory of Verse, The Hague, Mouton, 1966. |

|

1 A.J. Greimas and J. Courtés, Sémiotique. Dictionnaire raisonné de la théorie du langage, Paris, Hachette, 1979, p. 319. 2 See E. Tarasti, Existential semiotics, Bloomington, Indiana University Press, 2000. 3 J. Tynianov, Le vers lui-même, Paris, UGE, 1977. 4 “Zemic” for the simple reason that the orientation between its components takes the shape of the letter z. 5 W. Furtwängler, Keskusteluja musiikista, Porvoo, WSOY, 1951, p. 128. 6 A. and R. Pierce, Generous Movement. A Practical Guide to Balance in Action, Redlands, Balance Press, 1991, p. 14. 7 K. Kemppi, Liikuntarytmiikan perusteet, Porvoo, WSOY, 1969, pp. 1 and 3. 8 J.L. Hanna, To Dance Is Human. A Theory of Nonverbal Communication, Austin, University of Texas Press, 1979, p. 3. 9 R.L. Birdwhistell, Kinesics and Context. Essays on Body Motion Communication, Philadelphia, University of Pennsylvania Press, 1970, p. 4 and 21-23 (our stress). 10 See Karl Bücher’s classical work, Arbeit und Rhythmus, Leipzig, Teubner, 1899. 11 Cf. J.L. Hanna, op. cit., p. 29. 12 See, in the present volume, P.Aa. Brandt, “La petite machine de la musique”. 13 I. Krohn, Course of Music Theory I. Rhythm (Musiikin teoria oppijakso 1. Rytmioppi), Porvoo, WSOY, 1958 (2nd ed.). 14 See E. Tarasti, A Theory of Musical Semiotics, Bloomington, Indiana University Press, 1994, pp. 39-40. 15 Cf. J.-J. Rousseau, Dictionnaire de la musique, Paris, Chez la Veuve Duchesne, 1767, pp. 410-419. 16 R. Barthes, Le plaisir du texte, Paris, Seuil, 1975. 17 A. Lorenz, Der Ring des Nibelungen, Tutzing, Hans Schneiding, 1966, pp. 13-14. 18 F. Lerdahl and R. Jackendoff, A Generative Theory of Tonal music, Cambridge, MIT Press, 1985. 19 J. LaRue, Guidelines for Style Analysis, New York, W.W. Norton, 1970. 20 S. Kostka, Materials and Techniques of Twentieth-Century Music, New Jersey, Prentice Hall, 1999. 21 See S. Kostka, Materials and Techniques..., op. cit., p. 122. 22 D. Hocevar, Movement and Poetic Rhythm. Uncovering the Musical Signification of Poetic Discourse via the Temporal Dimension of the Sign, Helsinki, Acta semiotica fennica, XVII, 2003. 23 V. Zirmunskij, Introduction to Metrics. The Theory of Verse, The Hague, Mouton, 1966. 24 J. Mattheson, Der Vollkommene Capellmeister. Neusatz des Textes und der Noten (1739), Kassel, Bärenreiter, 2008. 25 W.J. Allanbrook, Rhythmic Gesture in Mozart. Le Nozze di Figaro and Don Giovanni, Chicago, University of Chicago Press, 1983, p. 18. 26 See R. Monelle, The Musical Topics. Hunt, Military and Pastoral, Bloomington, Indiana University Press, 2006. 27 L. Rowell, Music and Musical Thought in Early India, Chicago, University of Chicago Press, 1992. 28 Op. cit., p. 182. 29 Cf. R. Motiekaitis, Poetics of the Nameless Middle, Helsinki, Acta semiotica fennica, 2011. 30 See R. Monelle, op. cit., pp. 72-110. 31 G. Stefani, Introduzione alla semiotica della musica, Palermo, Sellerio. 1976. 32 K. Wahlström, Student-Centered Musical Expertise in Popular Music. Pedagogy and Hard Rock Groove : a Design-Based and Psychodynamic Approach, Thesis, University of Helsinki, musicology, 2021. |

|

______________ Résumé : Le rythme est un phénomène universel. Il apparaît sur le plan ontologique dans les diverses théories de la temporalité. C’est aussi un phénomène empirique à analyser dans toutes sortes de cas concrets. Il se manifeste tant sur le plan de l’énoncé que dans l’acte d’énonciation. Dans le cas de la musique, le rythme peut donc être inscrit dans la partition ou manifesté dans la performance. Il constitue à la fois une grandeur corporelle, une réalité psychologique, une dimension essentielle dans de nombreuses pratiques sociales, telles que les danses, et, en tant que symbole, il relève de l’esthétique. L’article aborde un grand nombre de cas, notamment la gemütlichkeit viennoise, le rubato de Bela Bartok, la tarantelle, la capoeira et la batuque : autant de variations rythmiques propres à différentes cultures. Resumo : O ritmo é um fenômeno universal : aparece em nível ontológico nas diferentes teorias da temporalidade ; por outro lado, é um fenômeno empírico a ser estudado em casos concretos. O ritmo aparece tanto no enunciado quanto no ato de enunciar. Se aplicarmos isso à música significa que o ritmo pode ser escrito na partitura ou manifestado na performance. O ritmo é uma entidade corpórea, uma realidade psicológica, que é determinante nas manifestações sociais como em várias danças, e o ritmo tem estética, ele é um símbolo. O artigo investiga um grande número de casos, desde o vienense gemütlichkeit ao rubato (Bela Bartok), tarantella, scanzione incitativa (Gino Stefani), Kalevala e 5/4 metro, capoeira e batuque, ou seja, variedades rítmicas em diferentes culturas. Abstract : Rhythm is a universal phenomenon : it appears on ontological level in the different theories of temporality ; on the other hand, it is an empirical phenomenon to be studied in diverse concrete cases. Rhythm appears either in the utterance (énoncé) or in the act of uttering (énonciation). If we apply this to music, it means that rhythm can be written down in the score, or manifested in the performance. Rhythm is a corporeal entity, a psychological reality, it is decisive in social manifestations like in various dances, and rhythm has aesthetics, it is a symbol. The article investigates a great number of cases, from the Viennese gemütlichkeit to the rubato (Bela Bartok), tarantella, scanzione incitativa (Gino Stefani), Kalevala and 5/4 meter, capoeira and batuque, i.e. rhythmic varieties in different cultures. Mots clefs : aesthetics, corporeality, enunciation, performance, temporality. Auteurs cités : Roland Barthes, Per Aage Brandt, Algirdas J. Greimas, Judith L. Hanna, Drina Hocevar, Raymond Monelle, Gino Stefani, Juri Tynianov, Viktor Zirmunskij. Plan : |

|

Pour citer ce document, choisir le format de citation : APA / ABNT / Vancouver |

|

Recebido em 11/03/2021. / Aceito em 04/04/2022. |